By Claudia Brauer | Versión en español aquí

My core message today is this: It is time to make climate change a priority in the translation industry and it is time to make translation a priority in the climate change discourse.

We have thousands of millions of individuals who need to receive life-changing data, information vital to their survival and the subsistence of their communities, and they might not be receiving it simply due to a language barrier. We need to remove this obstacle. We need to engage the language community and the leaders of efforts in the resolution of climate change issues. We need to empower local communities with information they can understand so they can take action.

A January 2018 blog by Morningside Translations on The Role of Translation in Fighting Climate Change talks about the vital role of translation and clearly states that “multilingual dissemination of research has become an increasingly critical factor in keeping people alive.” They further comment on the need not only to understand and convey meaning in the language of the recipients but also to understand “their intrinsic cultural perspectives, economics, and politics — which are critical for convincing local populations to implement changes.” From this blog, I also discovered that “there is even an emerging academic field called Ecolinguistics that investigates the role of language in the development and possible solution of ecological and environmental problems.” This is wonderful news for translators and linguists who would like to specialize in this new domain!

And it is also vital for the thousands of millions of people on earth who communicate in languages other than the “standard” languages we are so comfortably translating now. Any worldwide solution on the ground does require us to communicate in their national language or, better yet, their local dialect

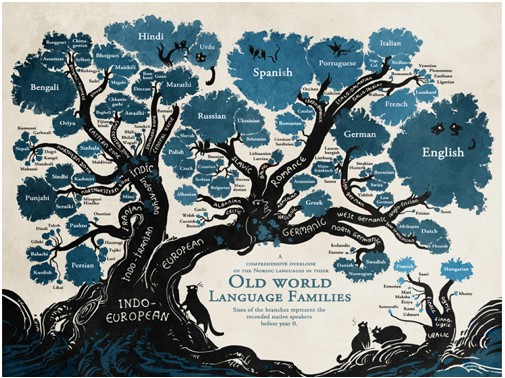

“How many languages are there in the world?” published by the Linguistic Society of America.

Lets now look at some statistics to make sure we understand the dimensions of the language conundrum. We, the “English/Spanish/French/Italian/German-centric” cultures, have really not much coverage worldwide, population-wise. For starters, just Arabic (270 million) and Bengali (170 million) speakers combined to surpass the number of English speakers. Why are global climate change documents not translated consistently into Arabic or Bengali?

But that is just the tip of the iceberg. About 1,000 million people speak Chinese-Mandarin. The 2nd most-spoken language in the world is Hindi, with some 500 million people, followed by Spanish, with 400 million and in the 4th place is English, with about 360 million.

This means that if we take all the English (360 million) speakers and all the Spanish (400 million) and the French (270 million), plus all the Italian (100 million), and the German (70 million), plus the Portuguese (220 million), Dutch (30 million) and Polish (40 million)and we put all of them together we still would barely start to reach the number of speakers of Chinese-Mandarin (1,000+ million) and Hindi (500 million).

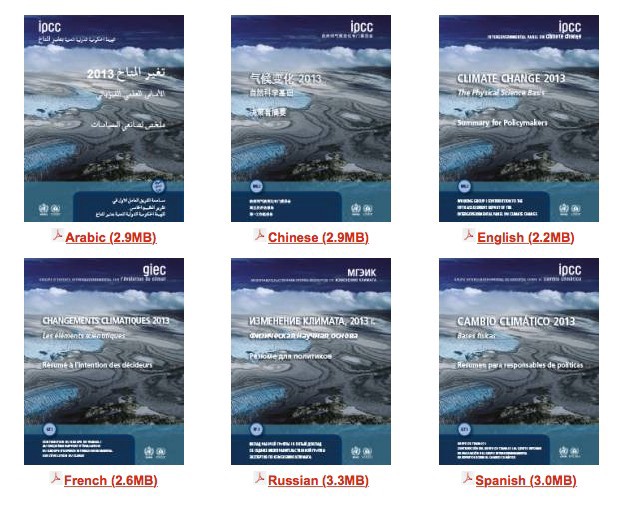

In 2013, the WMO/UNEP Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) did produce the above document in some of the widely spoken languages. This deserves recognition because it represents the type of efforts that the entire “Climate Change” community should be focusing on.

In general, we are busy covering just a fraction of the world’s 7,000 languages. If we translated all our materials into all the 10 languages mentioned previously in this post, we would still be reaching just above 1/3 of the population of earth. So, even in this “ideal” scenarios where we translate everything into the 10 most spoken languages, there are almost 5,000 million people “left behind”.

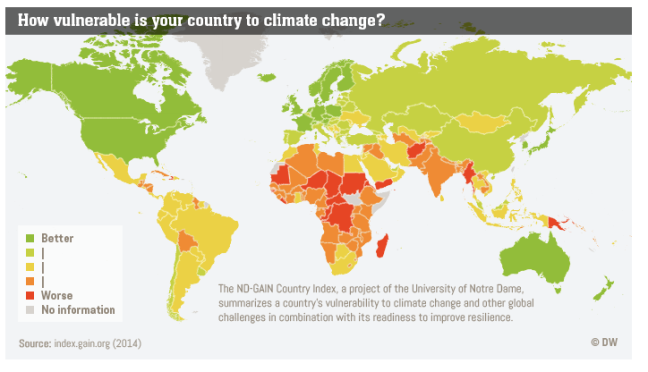

And where are these excluded individuals located?

NASA’s Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center (SEDAC) hosts a web page with some very interesting information by IPCC in terms of interactive maps and data on climate sensitivity and global distribution of vulnerability to climate change. It clearly shows some of these regions in danger to be located exactly where we have many of these untranslated languages and dialects. For starters, I am thinking of many parts of Africa and Asia, and even regions of Latin America where Spanish is not a mother tongue.

As a final note, on the upper end of the translation spectrum, there is a growing need for highly specialized translators in totally new fields of human knowledge, such as Paleoclimatology. Geoengineering, Ocean Acidification, Greenhouse Gases, Keeling Curve, and Carbon Footprint, to name but a few. Organizations such as TJC, which proudly offers “Global Warming Interpreters and Translators Worldwide” should be supported and imitated. Kudos! (P.S.: No, I have nothing to do with them or their work, but found it commendable.)

I will, therefore, close with my opening statement:

It is time to make climate change a priority in the translation industry and it is time to make translation a priority in the climate change discourse.

…

About UN CC:Learn

UN CC:Learn is a partnership of more than 30 multilateral organizations supporting countries to design and implement systematic, recurrent and results-oriented climate change learning. Through its engagement at the national and global levels, UN CC:Learn contributes to the implementation of climate change training, education and public awareness-raising.